Noticias

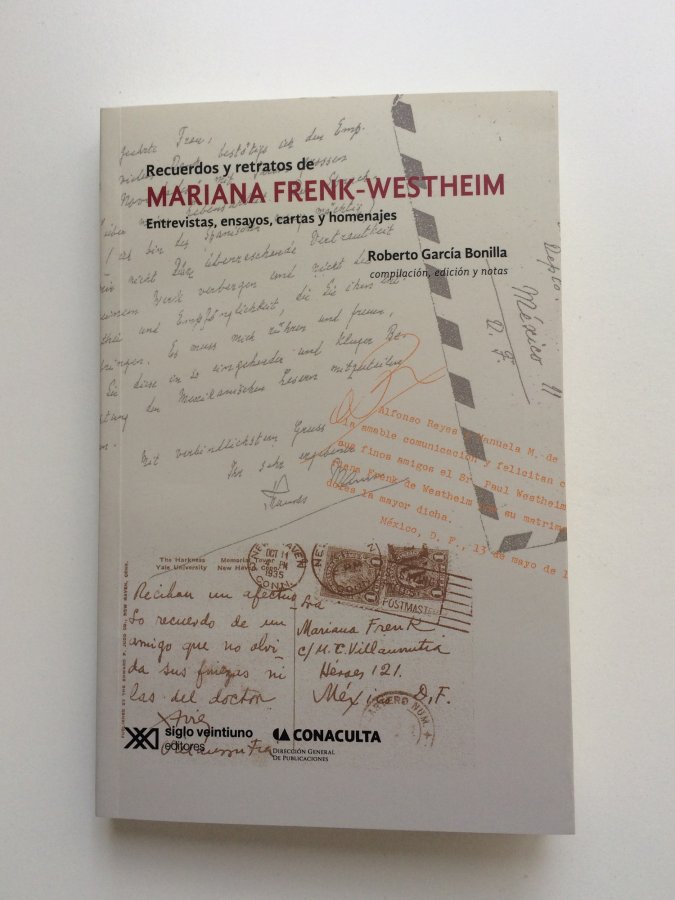

A co-publication by Siglo XXI and the Department of Culture

Mariana Frenk-Westheim, the conquest of the spirit by the language

July 14, 2016If we had to believe that every word has its own skill, Mariana Frenk-Westheim knew how to find and activate it in a constant enthusiastic courtship, both in her personal work, scattered mostly in magazines, newspapers and supplements and in the multiple translations she made.

Just the element that reveals the conquest of the spirit is the language that gives shape to herself, throughout the book, Memories and portraits by Mariana Frenk-Westheim. Interviews, essays, letters and tributes, compiled and annotated by Roberto Garcia Bonilla, co-published by Siglo XXI and the General Directorate of Publications of the Department of Culture.

A print with voices included, it is like going through a family album glossed with memories and anecdotes as subtle as evocative of a life that has been not only intense but splendid. A girl born subject of Franz Joseph of Habsburg, an Austrian girl educated as a Victorian in Bohemia, who at age 12, she said, she asked the Christmas man a book to study a foreign language which magnetism she felt since her childhood, the Spanish. Many years later she discovered that her ancestors lived "nearly a thousand five hundred years in Spain”, the blood tie that bound her to that language also surrounded the meaning of her life.

During a walk with her husband, Ernst Frenk and her mother-in-law, they stopped at a restaurant where they had reservations; as her husband was a doctor he had to be contactable so he asked the manager if there was a phone call for him he would be communicated. They left the mother sitting at the table, while the couple went to wash their hands. On their return they found the manager with Ernst’s mother standing up. When they asked what was happening, they were answered that the restaurant did not give service to Jews and as they were Jews, they had to leave the place. It was 1930 but they could see the likely development of the situation that was imminent, even as it happened, "it was impossible a normal brain could have imagined something like this”, so they decided they had to leave Germany.

In a bookshop in Hamburg, Mariana met a Mexican woman who suggested her Mexico as place to go with her family. Her first sensuous impression was: "Freedom". And Mariana became part of this country.

Running away from persecution and half blind, Paul Westheim who was her second husband, arrived years later in Veracruz, he was an art critic and a promoter of expressionism. He only knew a word in Spanish, esquina (corner) but as Mariana said, when he saw José Clemente Orozco’s frescoes and visited the Archaeological Museum, he said: "This is a country where a student of art can live ... I should have come 10 years earlier". Paul Westheim, when watching the sunset and the Mexican environment, he said with irony: "I owe all this to my Führer"

Her deep knowledge of literature, visual arts, romance languages and architecture enabled Mariana Frenk enter in intellectual circles, Thomas Mann, Amadis of Gaula (she read it at 16 in the library of Hamburg), Cervantes, Goethe, Heine, Kafka, Schubert, who esthetically formed her.

From a young age, while studying, she had given Spanish private lessons in Germany. In Mexico she sought to teach German in high school 1 at San Ildefonso, but without a title that credited her as a teacher she was rejected until Alfonso Reyes and Julio Torri gave her a letter of recommendation.

She had done translations since she was 6 so when she met Juan Rulfo through her daughter’s husband, she decided to translate Pedro Páramo into German. Then, she also translated El llano en llamas (The Burning Plain) and El gallo de oro (The Golden Cock), at Rulfo’s request. She was the one who in the original notion of traducere made him cross to the other side.

To translate was for her "to get under the skin and soul of the writer, to listen to their inner voices", but only succeeds who has the gift, because good translators are born, not made. The words are not translated, but culture, the vision of a world "and this is achieved by searching meeting points within the diversity, in the breadth of knowledge, in the blending of ideas”. And even though the translator is overshadowed, it is true that a good literary translation is a work of art.

A teacher of the Department of German Language at the National Autonomous University of Mexico, a master of literary theory, a translator at the National Polytechnic Institute, she worked with Fernando Gamboa at the Museum of Modern Art, a prolific contributor of the Supplement Mexico in Culture, Mariana spent little time on her personal work.

Surrounded by her own admiration for the great writers, it seemed that she was comparable to the ant that wanted to be an elephant. Nevertheless, she told about her creative process that "lady inspiration" had the very bad habit of visiting her at odd times, those in which she wanted to sleep, and she wrote without thinking about the reader, since "how to think of him if I do not know how he is? I do not know him and do not know what things are going to like him. I write with great pathos, what my heart or intelligence dictate me, or my intuition, that means freely”, she said.

Anyway, she published two books that collected her aphorisms, her poetry and her stories: Mariposa (Butterfly). Eternidad de lo efímero y …Y mil aventuras (The eternity of the ephemeral and…) ... And a thousand adventures).

The beauty of this tribute is announced from the beginning: a poem/gratitude written by José Emilio Pacheco: "Mariana, we owe you so much / That at least a grateful tribute / To you who never give in or rest/ I just want to say: for what you have been/ For us always, there is no forget: /The verses and roses for you”.

She knew everyone and everyone knew her, the volume houses a postcard by Xavier Villaurrutia, a poem written for her by Carlos Pellicer, a letter of gratitude sent by Thomas Mann, another one of Rosario Castellanos, and letters of tribute by Margo Glantz, Esther Seligson, Jaime Labastida, Peter Krieger, Antoni Peyrí, Fernando Benitez, among many others.

Mariana Frenk-Westheim considered herself a person who did not like at all to think about time, she ignored it; in that challenge, in that freedom and inexhaustible enthusiasm she created, she thought and she lived a fine life.

Roberto Bonilla Garcia (Mexico City) studied a degree in Hispanic literature, a master’s degree in Mexican literature and a doctorate in UNAM. He has practiced cultural journalism. He is the author of Visiones Sonoras (Sound Visions) (Siglo XXI Publisher/Conaculta, 2002), Un tiempo suspendido. Cronología sobre la vida y obra de Juan Rulfo (A time suspended. Chronology of Juan Rulfo’s life and work) (Conaculta, 2009); a compiler of Arte entre dos continentes (Art between two continents) by Mariana Frenk-Westheim (Siglo XXI Publisher/Conaculta, 2005). Currently, he is assigned editorial duties at UAM and UNAM.

Memories and portraits by Mariana Frenk-Westheim. Interviews, essays, letters and tributes, Compilation, editing and notes by Roberto Garcia Bonilla, Siglo XXI Publisher/Conaculta, 2014, 286 pp.

Mexico,Distrito Federal